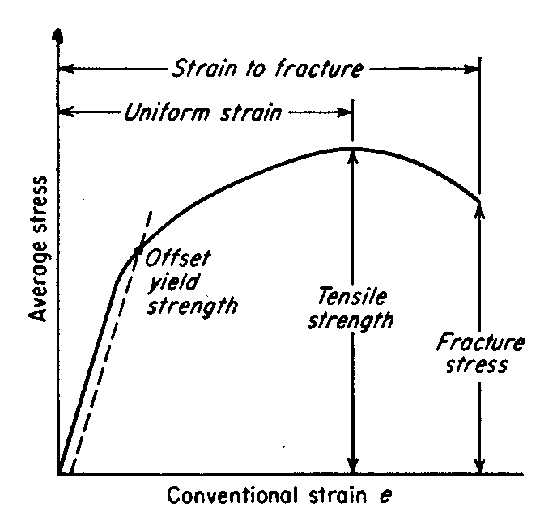

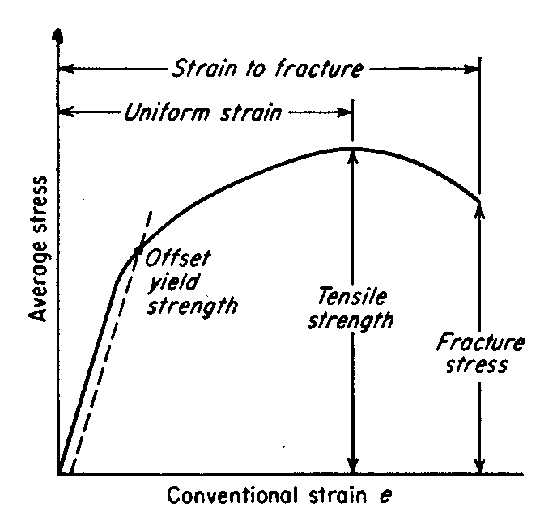

All steel has a Young's Modulus of 200 GPa (29 000 ksi) (This is the slope of the straight part of the graph) . Ultimate Strength runs from 300 - 400 MPa (peek of the graph), and the Yield is usually around 200 MPa (Where straight becomes curved).

In a test machine, you can stretch and shrink a steel bar up and down that straight part of the graph forever (Well, fatigue will kick in). But once you get into the curved part, unloading will follow a different path (See dashed line).

For structural purposes Yield strength is the limiting factor. In other words, you want your design to be limited entirely to the elastic (straight) region of the Stress/Strain chart. If you go into the plastic region, you're permanently deforming the material. (Although aircraft designers go well into the plastic region for reasons of weight).

The only reason to buy Stainless Steel is because you need the stainless property (i.e. finish work). It's far too expensive. For most purposes, normal rust protection measures are sufficient (Such as proper paint covering and maintenance, or even chrome plating for finished surfaces). Stainless steel has a lower Young's Modulus, and will deform more at low loads. However, this "Stretchability" makes it much tougher (but not stronger!). Think about snapping a dry twig vs. a green one.

Hardness is irrelevant for structural purposes. It becomes a factor in tool making and machine design, but not for simple load bearing applications.

EDIT:

Stiffness/Elasticity.

First we need to define strain as (Length of deformation)/(original length). This is a dimensionless quantity, but you can use mm/mm or in/in if you like to think about it that way. You could also think of it as %stretch/100 (That is, measured as PerUnit rather than PerCent -- base of 1 rather than 100)

Now we define stress as applied force over the cross sectional area. Think about it. The more force, the more stretch. The thicker the bar, the more resistance to stretch. So Stress is a combination of these two factors.

The deformation equation is Stress = E * Strain, where E is the Young's Modulus, or Modulus of elasticity. It has units of pressure -- Commonly expressed in GPa (Kn/mm^2) or Kpi (Kilopounds-force per square inch).

So a 1 mm^2 wire will double in length if loaded with 200 Kn of force -- Actually it will break well before that.

Bending:

This is complex, and we need to figure out the second moment of the cross sectional area. For a rectangle, this is I = bh^3/12 where b is the horizontal dimension, and h is the vertical dimension. This assumes that the load is downwards. If you're loading horizontally, then define vertical and horizontal in terms of the force direction.

Now we need to construct a loading function. This is a mathematical function that defines the force at every point on the beam.

Integrate that function. The result is the shear function.

Integrate it again. The result is the Bending Moment Function.

Multiply it by 1/EI (Young's modulus * the Moment of Inertia) This factor takes into account the Material Property, and the Geometric property.

Integrate it again. The result is the Deflection Angle Function (in Radians)

Integrate it again. The result is the absolute deflection function. Now you can plug in x (distance from origin) and receive the deflection in whatever units you were working with.